The “Umständliche und Wahrhaffte Beschreibung einer Land- und Leute-Betrügerin”: Confessional Polemic and Gender Transgression in Early Eighteenth-Century Germany

In recognition of Pride Month, we have chosen to highlight the rarely glimpsed but no less significant presence of LGBTQ+ people in early modern print culture. One such example was the polemical discourse surrounding the figure of Catharina Margaretha Linck whose extraordinary life was the subject of a ten-page anonymous pamphlet “Umständliche und Wahrhafte Beschreibung einer Land- und Leute-Betrügerin,” published in September 1720. Catharina was born in Prussia during the late 17th Century and spent the majority of their[1] life presenting as a man (although there are several periods where they present as a woman), serving in various armed forces and marrying a woman named Catharina Margaretha Mühlhahn at Halberstadt. Catharina was eventually taken to court in 1721 on the basis of this marriage and was subsequently convicted of sodomy, with an order for their execution issued by King Frederick William I.

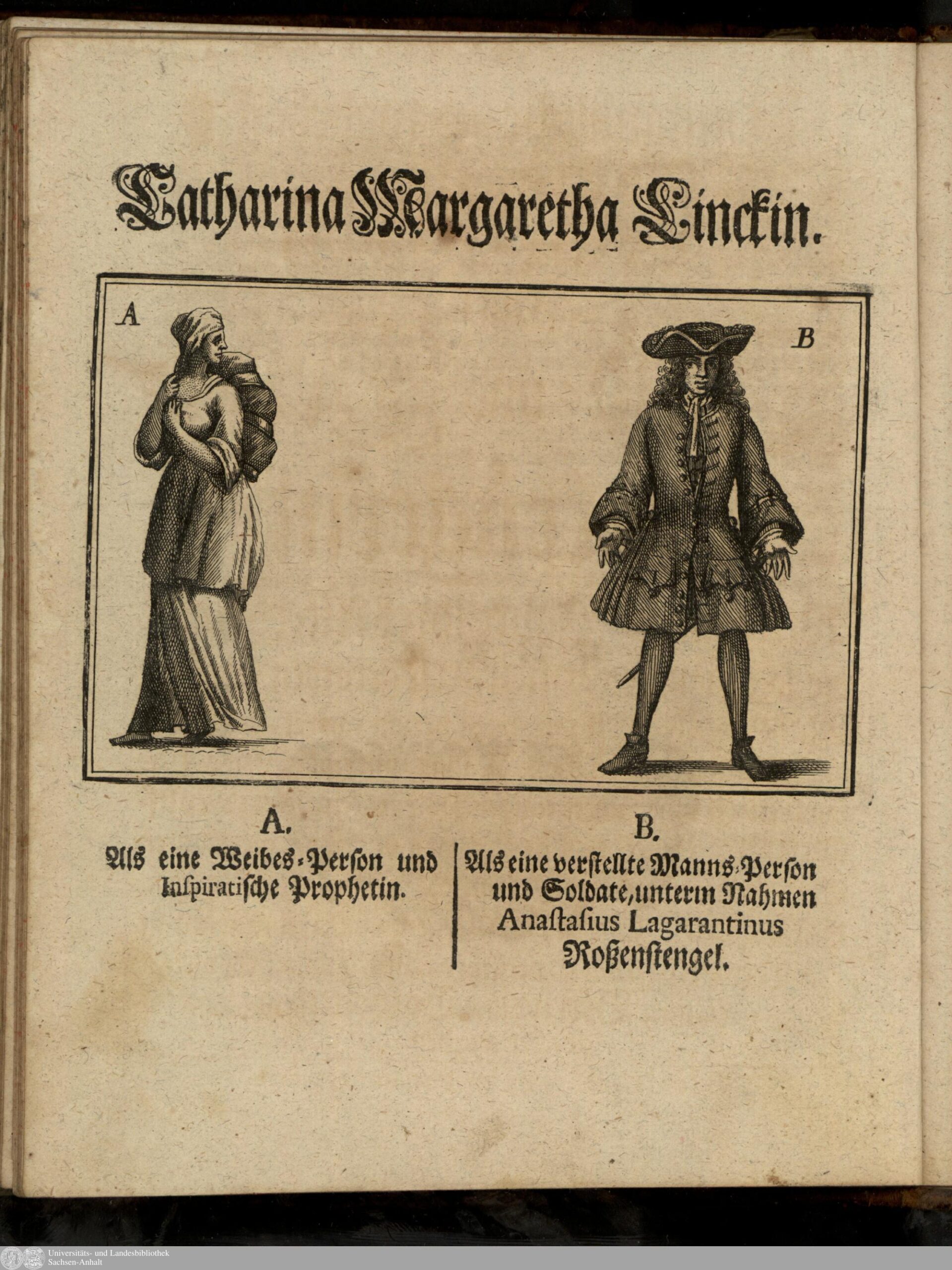

The pamphlet is written before the trial and the frontispiece provocatively depicts her in two guises: “as a woman and inspirational prophet” and “as a disguised man and soldier, under the name Anastasius Lagarantinus Rosenstengel.” This dual representation immediately signals the to the early modern reader the pamphlet’s polemical intent. Rather than seeking objective documentation, the work aims to weaponize Linck’s unconventional life against the broader religious movement known as the ‘Inspired’ (likely a form of Quakerism). The pamphlet then launches a frontal assault on the “so-called inspired,” accusing them of committing “the most damnable sins” under the pretense of godly living. The author then catalogues the Inspired’s alleged transgressions: refusing infant baptism, disregarding Biblical authority, and claiming direct divine revelation through “ridiculous postures” and ecstatic inspiration.

The second part of the pamphlet recounts Linck’s biography, but with significant chronological distortions that reveal the author’s propagandistic agenda. The narrative traces their adult baptism in Nuremberg and their prophetic activities, but erroneously connects them to Rosenstengel’s Anabaptist group, which only arrived in Halle in 1713 (a full decade after Linck’s ‘prophetic’ period). The various deliberate anachronisms suggest the author was more interested in creating a compelling narrative of religious deviance than in historical accuracy.

Linck’s same-sex (in the contemporary reading) relationship with their wife represents the pamphlet’s most sophisticated rhetorical strategy. While condemning the “most shameful filth” of their sexual relationship, the author frames this transgression as symptomatic of deeper spiritual corruption. The real scandal, he suggests, lies in Linck’s religious aberrations—their same-sex relationship merely provides evidence of their fundamental depravity. This approach transforms gender transgression into a metaphor for religious deception. Just as Linck deceived the world about their “true gender,” the ‘Inspired’ fabricate their supposedly divine revelations. The document’s manipulation of biographical and chronological evidence also provides insight into early modern practices of historical narrative construction, particularly within polemical contexts where rhetorical effectiveness took precedence over documentary accuracy. The pamphlet’s enduring significance lies not merely in its documentary value but in its demonstration of how individual transgression could be transformed into collective condemnation through careful narrative construction and strategic categorical conflation.

A digitised copy of the pamphlet can be accessed through the University and State Library of Saxony-Anhalt : https://digital.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/hd/content/pageview/222369

Image: urn:nbn:de:gbv:3:3-7125-p0004-6

This brief overview draws extensively from Angela Steidele’s groundbreaking study: In Men’s Clothes: The Daring Life of Catharina Margaretha Linck, alias Anastasius Lagrantinus Rosenstengel, executed in 1721. Biography and Documentation. Originally published in Cologne: Böhlau, 2004, revised and supplemented with newly discovered sources. Berlin: Insel, 2021. This work provides the definitive scholarly examination of this remarkable historical figure and the sources surrounding her life.

[1] The pronouns ‘they/them’ are used here in recognition of Catharina’s unknown gender identity. N.B. Contemporary historical sources (not written by Catharina) use ‘she/her’.